|

Foot and Mouth Disease

Sometimes events become so dramatic, they force us to reevaluate our actions. The outbreak of foot and mouth disease (FMD) in Britain in March 2001 and the Governments 'stamping-out' policies have resulted in the mass slaughter and burning of cadavers of cloven-hoofed animals. The action is the attempt to stop the spreading of the virus by eradicating it without using vaccination to protect healthy animals. This way, the highly contagious virus can only be stopped by killing also healthy animals within a certain radius of an infected farm (on March 26 set at 2 miles).

The reaction clearly demonstrates a catastrophic outbreak of a disease threatening something vital. It may come as a surprise to many of us not involved in agribusiness that this vital object is international trade, i.e., export restrictions on meat and livestock for countries that are not officially FMD-free. The first thing that comes to mind while watching thousands of cadavers burning is why animals are not being protected by vaccination - which is available - instead of killing infected and healthy animals. The scope of the stamping out procedure rises indeed the ethical question of why thousands (and currently the number is reaching close to one million causing the British government to have a new look at vaccination; note added March 28 the government started vaccination with the approval of the European Union) animals should be sacrificed in the name of international trade if immune protection is readily available. The burning is a choice guided by international trade rules (most notably GATT, the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs and guidelines in Chapter 2.1.1. of the International Animal Health Code) that allow protectionist measures of FMD-free countries against non FMD-free countries. Britain does not want to loose its FMD-free status. To achieve this it is willing to destroy perfectly good meat. There is of course an irony in all of this because these cows, pigs, and sheep are eventually slaughtered for the benefit of human meat consumption. So why should one rise an ethical question about premature death of animals who would be sacrificed anyway? It is questions like these that need to be answered independent of the real issues on economic consequences and how to avoid severe financial losses for British farmers.

Ethical questions deal

with our actions with someone else paying the price. Here the price

for economic trade rules is paid for by animals. The British lesson

will be important for the US. As long as an FMD-free status can

be maintained the GATT rules are a great way to protect American farmers

from competitors. Yet by avoiding vaccination American ranches are

sitting ducks for the virus and an outbreak seems a matter of time.

If FMD were a health issue worldwide eradication of the virus would

be a priority for industrialized nations. It worked for polio*,

it can work for foot and mouth disease. If eradication proofs elusive

and too expensive, why not go for world wide vaccination? Such a shift

in global farming policy would also make for good economic policy

toward developing nations. Cash and debt-relieve alone no longer guarantee

solutions for strong economic development around the globe. Cash infusions

need to be complemented by eliminating protectionist trade barriers.

If Americans were sincere about helping developing countries to become

economically more independent, we would vaccinate our cows, let them

sell their meat at competitive prices (as long at it is safe

to eat), and could at this very moment help saving thousands of healthy

animals from being burned in the name of protectionism.

Home | In the news Copyright © 2001-2006 Lukas K. Buehler |

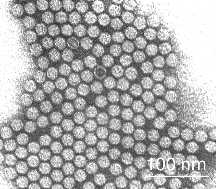

Viral particles as seen

by electron microscopy

Viral particles as seen

by electron microscopy